It was “Care Free/Car Free Day” at school last Thursday.

Some students walked in, starting out before dawn. Many rode bikes. Those near a line took the light rail. My wife has been suggesting for years that I try our local option for public transportation, so I caught the bus.

Check out this great essay by Frank Kovarik about the layers of history and culture on my route.

—

7:05 a.m.

My wife offered to give me a ride to the bus stop on her way to work. Hopping out with my back pack, I realized I had no money.

“Here” she said, handing me a $20, justifiably a little annoyed at my spaciness. “You’ll have to walk somewhere to get change. What time does the bus come?”

I had no idea.

“You didn’t check on-line?” she asked, frustration rising.

“The site was pretty confusing. I’m sure one will come along soon enough.”

There were cars behind us and she was going to be late if she waited to see what became of me.

“Go ahead, I’m good.”

With a skeptical “OK then, good luck!” she turned her attention to her own oncoming day. The door closed with a “clunk” of finality and her car pulled away.

What came next was one of those strange moments of dislocation you have when your car breaks down. You stand on the side of the road with oblivious traffic going by. Or maybe a shock or misfortune pulls you out of your routine and onto life’s sidelines. Suddenly, you’re watching everyone else going about their normal business. Your mind mutters at you in existential nervousness: “Who are these people and where are they all going? What do they think of me standing here? Do they even notice? And where am I going, anyway? How will I ever get there?”

What came next was one of those strange moments of dislocation you have when your car breaks down. You stand on the side of the road with oblivious traffic going by. Or maybe a shock or misfortune pulls you out of your routine and onto life’s sidelines. Suddenly, you’re watching everyone else going about their normal business. Your mind mutters at you in existential nervousness: “Who are these people and where are they all going? What do they think of me standing here? Do they even notice? And where am I going, anyway? How will I ever get there?”

Fortunately, another more buoyant and literary voice in my head also had me feeling like Cary Grant waiting for George Kaplan in “North By Northwest.” It said something like: “This is interesting. I have no change. Nothing is open on this stretch of road. This story could go in any number of directions. I wonder how this day will end?”

7:12 a.m. I had an important meeting at 8:05. I guessed the trip to be about 11 miles. I started my commute walking east.

Here’s how the rest of the day went “by the numbers:”

200 meters down the road was a tiny, very lonely looking cinder block building. I assumed it was an abandoned husk. “Open” said the sign in the window and in painted lettering above the door: “Trog’s.”

200 meters down the road was a tiny, very lonely looking cinder block building. I assumed it was an abandoned husk. “Open” said the sign in the window and in painted lettering above the door: “Trog’s.”

I knew immediately the building reminded me of something but I couldn’t say what. A small, old gentleman was inside behind an ancient counter. Not a single product to buy in sight, so I just had to ask for the change. “What’ll it be?” he asked. I didn’t understand the question. “The bills. What do you want?” Suddenly realizing I didn’t even know what the fare was, I asked for a 10, a 5 and 5 one’s. He handed it over. I thanked him and walked back out to the road to stand at the nearest bus stop sign.

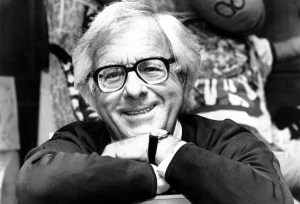

Edward Hopper's "Gas"

Looking back downhill at the shop, I saw him walk slowly out to the old-style pumps in front. He got out a rag and began wiping down the concrete posts guarding the gas. That’s when I knew where I’d seen the building–and its proprietor–before.

My eyes were back on the road, looking west for the bus. There was little else to do but stare at the pavement, so I did. As soon as my eyes found a patch of it with new grass growing up through the cracks, it felt so familiar. As a kid I’d  stared in boredom at pavement thousands of times. It had been a very long time, but wherever and however such a specific category of experience is stored in memory, it came over me like physical sensation. I was sweating just a bit already on a warm morning. My limbs were loose and strange and my skin was breathing. It was odd to be wearing a tie.

stared in boredom at pavement thousands of times. It had been a very long time, but wherever and however such a specific category of experience is stored in memory, it came over me like physical sensation. I was sweating just a bit already on a warm morning. My limbs were loose and strange and my skin was breathing. It was odd to be wearing a tie.

When the phone buzzed in my pocket I was still elsewhere and it took a second or two for me to think of what it was.

“Hey, it’s me. I checked. Your bus is #57. It comes at 7:33. It’s two bucks. Ok? Bye Bye.” I was being taken care of. It happened that way all day.

7:38 a.m. The bus arrived.

I climbed in, slipped bills in awkwardly as directed by the worn illustration on the stainless steel fare counter: George-up-crown-facing-east. I settled into a seat. There were 13 of us aboard, seating capacity about 46. A fairly late bus for real working people. The passengers talked in familiar, tired, morning-work-day tones, the folks closest to me about Sea Monkeys: those tiny, shrimp-like creatures that come

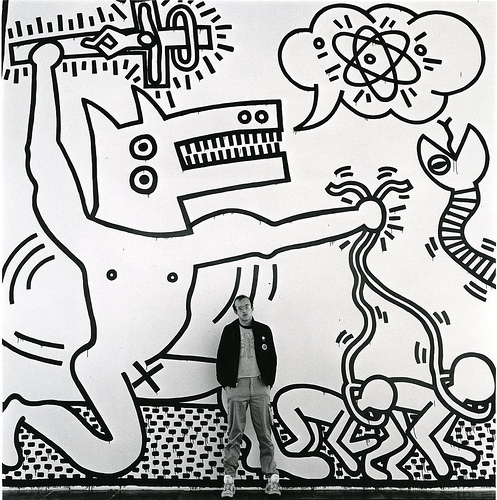

Image at The Comic Book Catacombs

powdered in a bag by mail. A guy said to his skeptical seat mate: “No, I’m serious. You just put this stuff in water and you see these tiny monkeys swimming around.” She wasn’t convinced and he couldn’t explain it any further. Guy had probably been a Boy Scout. And she had probably never seen a copy of “Boy’s Life.”

Some folks just stared into their cell phones. I wondered if in 20 years anyone would be talking to someone sitting next to them when they could be tuned in to almost anything anywhere inside their heads. Would the elites be tuning in on custom “feeds” they bought and built for themselves to maximize their opportunities? Would regular Joe’s and Jane’s have commercial streams of sights and sounds beamed into their heads as they went from Rockhill to Brentwood to Maplewood?

This route is a straight shot: a single corridor extending from the near county well into the city, through 5 gritty, established inner-ring suburban municipalities. The bus pulled into a light rail connection station at one of them and sat there for 10 minutes. The driver reassured me I could stay aboard. I asked twice just to be sure.

7:55 a.m. We got going again and I called in to let them know I’d be late for the meeting.

8:23 a.m. I stepped down onto the pavement a few blocks from school. By 8:33 I was at the conference table, blaming the bus. There were knowing snickers, eyes rolling all around. We were all mocking the bus. But I felt guilty doing it. The trip had felt so real.

—

It was a full day of meetings, paper and projects, but my class met in the middle of it all and we were talking numbers. Were they real or just human invention? Did they reflect the universe or the mind?  Was the order they helped us discern really there in the universe as testimony to God or were we imposing the order on impossible complexity and fundamental chaos? The previous day we’d had a guest speaker on infinity. His class felt to me like the presentation of a 40-minute zen koan. He had us count, group, sort and subdivide infinity and then, when we’d worn ourselves out, come back to it as something that couldn’t be grasped. He ended with a meditation on the Eucharist: the infinite contained in a wafer of bread. We ended our unit on my bus-travel-day suggesting that maybe math didn’t say as much about God by means of what was out there as much as it pointed to the infinite–and so to God–in here. Wasn’t that another way of saying what we believe about the transcendental nature of human beings, what we mean by faith in Christ?

Was the order they helped us discern really there in the universe as testimony to God or were we imposing the order on impossible complexity and fundamental chaos? The previous day we’d had a guest speaker on infinity. His class felt to me like the presentation of a 40-minute zen koan. He had us count, group, sort and subdivide infinity and then, when we’d worn ourselves out, come back to it as something that couldn’t be grasped. He ended with a meditation on the Eucharist: the infinite contained in a wafer of bread. We ended our unit on my bus-travel-day suggesting that maybe math didn’t say as much about God by means of what was out there as much as it pointed to the infinite–and so to God–in here. Wasn’t that another way of saying what we believe about the transcendental nature of human beings, what we mean by faith in Christ?

5:00 p.m. Leaving my office and out into the alley behind school.

Bi-State Kiosk Poster

It was a 5-minute walk back to the bus stop, but this time I was in no hurry. I stepped out of the sun into the kiosk at the stop. A young boy about 5 years old sat on the bench with his young mother. He was eating chips and drinking a soda. She sat there staring straight ahead or at her cell phone. The boy wanted to talk.

“Mom, what’s 10 x 10?”

“100. Why are you asking me that?”

“Just something I was thinking about.” I could see this was a very clever kid, his face and voice alive with constantly changing expression and musical intonations.

“How about 20 x 20?” he sang out next. “400” she replied, still staring straight ahead.

“30 x 30?” She hesitated for just a second. “900.”

40 x 40?” She smiled and looked over at him now. “What do I look like, a calculator?” “1600.”

He giggled now, knowing he had her going. “50 x 50?”

“Now that’s enough!” she said laughing herself.

He tried one more time:”60 x 60?” She looked like she was thinking about this one, then scolded: “I told you I’m not a human calculator!”

“I wish I was a human calculator!” he said brightly. I couldn’t resist him anymore.

“I recognize a smart boy when I see one!” I said. That got his mom and I talking.

She turned my way and asked if this bus was usually on time. One trip and someone actually thought I was a veteran! She explained that she had a 5:30 doctor’s appointment at a clinic in 10 minutes.

“Buses are always late and they think they can just keep raising the rates on us.”

The boy jumped in: “You going to be late, Mom?”

“No, you are the one who is gonna be late! its your appointment.”

“Oh, yeah…” his voice trailed off as it hit him that he had to see the doctor. Then: “Oh no!”

“Oh, yeah…” his voice trailed off as it hit him that he had to see the doctor. Then: “Oh no!”

5:23 p.m. The west-bound bus arrives.

Math Boy got on just ahead of me, turned around and gave me a big, sparkling smile. I got a full-face exposure to all of that curiosity, all of the infinite potential in that face.

I paid the $2 fare and asked the driver if this bus would get me back to my corner, 11 miles west. No. I’d have to change buses at the station. A transfer would cost 75 cents. Before I could stop myself I said: “I only have a $5.” If there’d been any doubt, now he knew I was green.

He said: “You can ask someone for change or a transfer they don’t need.” But he saw my discomfort and shouted back almost immediately: “Anybody back there have change or a transfer they don’t need?”

A young man announced without expression that he had one and held it up. I took it and thanked him. Two more real veteran commuters coming through for the pilgrim.

5:40 p.m. Math Boy and his Mom reach their stop. 10 minutes late. That should be close enough. I hoped it was just for a check- up.

5:40 p.m. Math Boy and his Mom reach their stop. 10 minutes late. That should be close enough. I hoped it was just for a check- up.

5:46 p.m. We’re back at the light rail transfer station. The driver remembered that I needed #57 westbound. It was waiting, poised to depart. Two quick blasts on the horn told the bus to wait for me. “Make your move!” he shouted back. I was aboard the next bus in 20 seconds. We were moving in 30.

Bus #57, bound for far West County, was clean. New. And the AC was working on a warm day. I realized how shabby the last bus was and found myself wondering if it was just a coincidence that we’d left the city for the county.

There were 20 of us on board, seating capacity for 46. One of the signs  above the passengers was an AIDS awareness ad. Two flawlessly beautiful, sensuous African-American faces poised inches from one another. Both the message and the medium felt so intimate, so real. I realized I hadn’t taken in ads that felt this way with any regularity since I was a graduate student riding the subway in the Bronx.

above the passengers was an AIDS awareness ad. Two flawlessly beautiful, sensuous African-American faces poised inches from one another. Both the message and the medium felt so intimate, so real. I realized I hadn’t taken in ads that felt this way with any regularity since I was a graduate student riding the subway in the Bronx.

6:09 p.m. I texted my wife to let her know I was on my way and would be home soon. Her message came back: “Glad to hear it, I was starting to wonder. Do you want me to pick you up at the bus stop?”

It was two miles and the prospect of a long walk on a spring evening sounded pretty good.

“No, I’ll think I’ll leg it in.”

“See you soon. Keep it real, Dude.”

For a “Care Free/Car Free Day”–or any other day for that matter–that’s advice I hope to keep counting on.